The first person to survive plunging over Niagara Falls in a barrel was Annie Edson Taylor, a former schoolteacher. She hoped to achieve financial stability by doing the act of daredevilry, on her 63rd birthday, 24 October 1901. She later said she would rather be blown to pieces by a cannon than ever do it again. If you look carefully at the photograph above, you can see the cat that survived the 51-meter (167-foot) plunge in a wooden pickle barrel, 2 days before Annie did it. Miss Taylor initially succeeded in her effort to achieve fame and fortune following the harrowing stunt, but her manager ran off with her barrel. She spent a great deal of money on detectives, trying to locate the barrel and get it back, and consequently, she passed on destitute 20 years later at 83 years of age. The moral of the story? Guard your barrel carefully or you will go broke trying to get it back . . . no, wait - that can’t be right . . . maybe it is: Be careful of the kind of people you associate with, because they could steal your hard-earned success away from you and leave you with nothing.

|

Tomato Millionaire

An unemployed man went to apply for a job as a janitor. The manager arranged for him to take an aptitude test. After the test, the manager said, “You will be employed at the minimum wage of $5.75 an hour. Let me have your e-mail address, so that I can send you a form to complete and tell you where to report for work on your first day. Taken aback, the man protested that he had neither a computer nor an e-mail address. To this, the manager replied, “Well, then, that means that you virtually don’t exist and can therefore hardly expect to be employed. Stunned, the man left. Not knowing where to turn and having only $10 in his wallet, he decided to buy a 25-pound flat of tomatoes at the supermarket. Within less than 2 hours, he had sold all of the tomatoes individually at a 100-percent profit. Repeating the process several times more that day, he ended up with almost $100 before going to sleep that night. And so it dawned on him that he could quite easily make a living selling tomatoes. Getting up early every day and going to bed late, he multiplied his profits quickly. After a short time, he acquired a cart to transport several dozen boxes of tomatoes, only to have to trade it in again so that he could buy a pickup truck to support his expanding business. By the end of the second year, he was the owner of a fleet of pickup trucks and managed a staff of a hundred formerly unemployed people, all selling tomatoes. Planning for the future of his wife and children, he decided to buy some life insurance. Consulting with an insurance adviser, he picked an insurance plan to fit his new circumstances. At the end of the telephone conversation, the adviser asked him for his e-mail address in order to send the final documents electronically. When the man replied that he had no e-mail address, the adviser is stunned, “What, you don’t have e-mail? How on earth have you managed to amass such wealth without the Internet, e-mail, and e-commerce? Just imagine where you would be now, if you had been connected to the internet from the very start!” After a moment of thought, the tomato millionaire replied, “Why, of course! I would be a janitor!” Moral of this story: 1. The internet, e-mail, and e-commerce do not need to rule your life. 2. If you don’t have e-mail, but work hard, you might still become a millionaire. 3. If you got this story by e-mail, you’re probably closer to becoming a janitor than you are to becoming a millionaire. 4. If you do have a computer and e-mail, you have already been taken to the cleaners. by Author Unknown Is this a fictional story? We don’t know, but we think it is interesting enough to share with others because the lessons within it might be reasons for all of us to pause and think. Who is Dave Thomas? Rex David ‘Dave’ Thomas is known as the founder of the Wendy’s restaurant chain. Before starting Wendy’s, he helped to save the KFC (formerly known as Kentucky Fried Chicken) franchise from going out of business. Mr. Thomas first worked at a Knoxville restaurant as a youngster of 12 years of age, from which he was eventually fired due to a misunderstanding with his boss about a vacation. At 15, he worked at a Hobby House Restaurant in Fort Wayne, Indiana. His father and step-family, at that time, were moving, but he decided to drop out of high school and stay in Fort Wayne. He moved into the YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association) and started working full time at the Hobby House. This worked out well for him, because through his job at the Hobby House Restaurant, he met none other than Colonel Sanders himself, the founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken, who would become his mentor. Many years later, in 1962, after a stint in the Korean war as a cook in the United States Army, for which he volunteered, Mr. Thomas invested in and was placed in a managerial position over four of Colonel Sanders’ KFC restaurants that were failing. He saw that one of the problems with KFC, and all fast food restaurants of the day, was that they had complicated menus. He worked with Colonel Sanders to drastically simplify the menus, focusing on a few signature meals. This single change helped to turn around the KFC franchise; and, though it was a small thing, it helped revolutionize fast food restaurant menus all over the world. Even to this day, the staple of most fast food restaurants is their overly simplistic menus, focusing on a handful of signature meals. After he had turned these failing KFC restaurants around, he then sold his stake in them back to Colonel Sanders for a significant profit over what he originally paid, receiving $1.5 million in the sale. He took the money and opened the first ‘Wendy’s Old Fashioned Hamburgers’ on 15 November 1969, the restaurant being named after his fourth child, Melinda Lou Thomas. You might ask, “How did they get ‘Wendy’ out of Melinda Lou Thomas?” This was a nickname given to her, because she could not pronounce her own name when she was young. She would say, “Wenda,” which is how she got the nickname ‘Wendy’ and how the restaurant in turn got its name. 6,000 restaurants later, Wendy’s became the third largest hamburger fast food restaurant in the world, with annual revenue of about 7 billion dollars, lagging just behind Burger King with its 12,000 restaurants and McDonald’s with its 31,000 restaurants.

As a child, Dave Thomas’s favorite restaurant was Kewpee Hamburgers, the second-ever chain of hamburger fast-food restaurants. Their staple items were square hamburgers and thick malt milkshakes, much like Wendy’s. Mr. Thomas is the person responsible for introducing the KFC trademark sign, featuring a revolving red-striped bucket of chicken. He was the first person to successfully implement a drive-through window in a restaurant, which is of course, now available at nearly all fast food restaurants. Wendy’s was the first to successfully create a ‘fast food’ style restaurant that didn’t pre-cook its food or used pre-made frozen items. Dave Thomas credited his ability to do this with the know-how he gained in cooking for more than 2,000 soldiers daily while in the United States Army. Dave Thomas never met or knew who his biological parents were, other than that they were of Greek descent and that his biological mother was single and dirt poor due the Great Depression of the 1930’s. Mr. Thomas became a Freemason, a member of the Shriners, and an honorary Kentucky Colonel. Realizing that his success as a high school dropout might convince other teenagers to quit school, something he later admitted was one of his life’s greatest mistakes, he later became a student at Coconut Creek High School, and in 1993, he received a G.E.D. (General Education Diploma, an equivalent to a High School Diploma), being voted by his classmates as, “most likely to succeed.” He appeared in more than 800 Wendy’s television commercials, achieving the record for “Longest Running Television Advertising Campaign Starring a Company Founder,” according to the “Guinness Book of World Records.” Being adopted himself, he founded the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption to help children find homes, and to help them and their new families after the adoption. In 1979, Mr. Thomas’ rags-to-riches story earned him the Horatio Alger Award from the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans. Upon the passing of his mentor, ‘Colonel’ Harland Sanders, founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken, Mr. Thomas ordered that all flags at Wendy’s franchises be flown at half-staff. Dave Thomas himself passed on at 69 years of age on 8 January 2002. If Dave Thomas could do great things with burgers, what can you do, with what you have, where you are? Wendy’s has more than 6,700 restaurants around the world today. For more information, visit https://www.wendys.com/. Hang in There

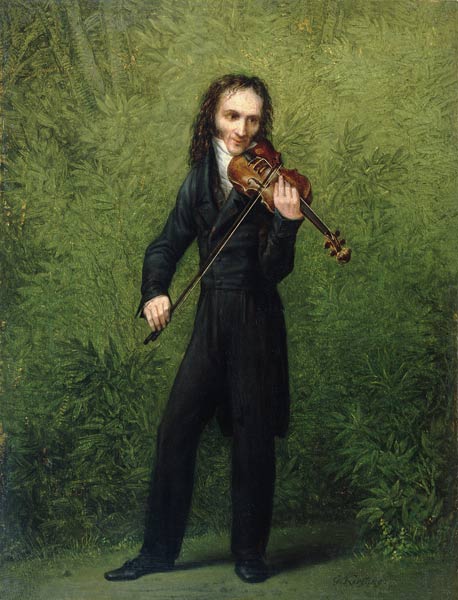

Niccolò Paganini (27 October 1782 - 27 May 1840) was a well-known and skilled violinist. He was also recognized for being a great showman with a quick sense of humor. One of his most memorable concerts was in Italy with a full orchestra. He was performing before a packed house and his technique was incredible, his tone was fantastic, and his audience was completely captivated. Toward the end of his concert, Paganini was astounding the concert attendees with an unbelievable composition, when suddenly one string on his violin snapped and hung uselessly. Paganini frowned briefly, shook his head, and continued to play, improvising beautifully. Then, to everyone’s surprise, a second string broke. And shortly thereafter, a third. Almost like a slapstick comedy, Paganini stood with three strings dangling from his Stradivarius. But instead of leaving the stage, Paganini maintained his ground and calmly completed the difficult number on the one remaining string. For those who might doubt the statistical probability of the series of events described in the anecdote above, consider that the strings were made of natural material, all derived from exactly the same source, all of exactly the same age and amount of wear from use, and when the humidity and temperature and pressure reached the right point, the strings lost their structural integrity all within the span of a musical performance. This was no remarkable coincidence, just a scientifically plausible occurrence. For a moment in time, conditions existed such that there was a ‘One-String Paganini’ playing before an audience. There are many One-Stringed Paganinis making their way through life. You might never suspect who among the people you meet in your day-to-day life is one of them. You might be one yourself for all that is known. If that’s the case, hang in there, keep playing on your one remaining string, and every day continue to ‘Make Fun Of Life!’ Image: Niccolò Paganini (about 1831) portrait by German painter Georg Friedrich Kersting. Industrialists

John Davison ‘J. D.’ Rockefeller was only thirty-three when he owned ninety percent of all American refineries and all the main pipelines and oil cars of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Within a few years he was the first billionaire in history. He lived most of his life more simply than most stock-brokers, like a frugal Scandinavian monarch. By his bedside in his New York house he had always on hand his Bible, though it lay on top of his bedside safe. At sixty, penitence set in. He was very much a Victorian in his capacity to rationalize his energy as the engine of God. And, as happened with many more of the money barons, the coming on of arthritis convinced him that he had made all his money for the public good. So, with complete sincerity, he disbursed it. Through a foundation created in his own name, he gave $530,000,000 for worldwide medical research. I must say that he is the only philanthropist I can think of who gave away his fortune with no strings binding its use. He was photographed everywhere doing folksy things - attending a county fair, teetering on the putting green, marrying off a couple of midgets for charity - to prove that even Rockefeller was as mortal as the rest of us and that, though he was a kind of monarch, he had the common touch. As he moved into his nineties people began to doubt his mortality, but the news that he was restricted to a gruel and Graham cracker diet brought some consolation to the poor and healthy. When he died, at the age of ninety-eight, it was as if an emperor had gone. (. . .) There were not many men like Rockefeller, but it didn’t take many to constitute a cabal of real national, continental power that overshadowed the elected power of the Presidents of the United States. There was Henry Clay Frick, who turned coke and iron ore into gold, and E. H. Harriman, who collected railroads the way other men collect stamps. There were Harriman’s rival, James J. Hill, and his ally, John Pierpont Morgan, Senior, whose specialty was money itself. And there was Frick’s sometime friend and sometime enemy, Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie had three specialties: steel, making money, and giving it away. The son of a poor weaver, he was born in a stone cottage in Dunfermline, Scotland, in 1835, at a time of such depression that in the revolutionary year of 1848 the family took off for America and for a squalid house in a grimy town called Pittsburgh. The father went back to weaving and the mother went back to stitching shoe leather; it was not much of a New World for them. But their twelve-year-old boy was as shiny as an apple and as lively as a squirrel, and he went hopping up the golden ladder rung by rung: from bobbin boy to telegraph messenger to railroad clerk, to superintendent to director. Until iron entered his career, if not his soul, and finally steel. At the turn of the twentieth century he wrote an article that ended with the heroic phrase: “Farewell, then, Age of Iron; all hail, King Steel!” He was really proclaiming his own coronation, because he foresaw before anybody the infinite possibilities of steel, for bridge building and steamships, for elevators and knives and forks. Make steel, and make it cheap, and you could own the industrial empire of the new century. Before he was thirty, he had bought a large tract on Oil Creek but soon turned from oil to building, and buying up, iron and steel mills and their tributary coal and iron fields, and then the railroads that brought their products to the Great Lakes docks, and a steamship line that took them on to Europe. His monopoly of steel helped him to weather the depression of 1892, and nine years later he graciously permitted the United States Steel Corporation - formed for the purpose - to buy him out for $250,000,000. And then he abdicated, or retired, to a castle in the eastern highlands of Scotland. He was sixty-five and he had eighteen years yet to live. And he now began the career of lavish philanthropy that made his name known around the world. Carnegie exemplifies to me a truth about American money men that many earnest people fail to grasp - which is that the chase and the kill are as much fun as the prize, which you then proceed to give away. by Alistair Cooke: “America” (1973) Peter of Cortona A little shepherd boy, twelve years old, one day gave up the care of the sheep he was tending, and betook himself to Florence, where he knew no one but a lad of his own age, nearly as poor as himself, who had lived in the same village, but who had gone to Florence to be scullion in the house of Cardinal Sachetti. It was for a good motive that little Peter desired to come to Florence: he wanted to be an artist, and he knew there was a school for artists there. When he had seen the town well, Peter stationed himself at the Cardinal’s palace; and inhaling the odor of the cooking, he waited patiently till his Eminence was served, that he might speak to his old companion, Thomas. He had to wait a long time; but at length Thomas appeared. “You here, Peter! What have you come to Florence for?” “I am come to learn painting.” “You had much better learn kitchen work to begin with; one is then sure not to die of hunger.” “You have as much to eat as you want here, then?” replied Peter. “Indeed I have,” said Thomas; “I might eat till I made myself ill every day, if I chose to do it.” “Then,” said Peter, “I see we shall do very well. As you have too much and I not enough, I will bring my appetite, and you will bring the food; and we shall get on famously.” “Very well,” said Thomas. “Let us begin at once, then,” said Peter; “for as I have eaten nothing to-day, I should like to try the plan directly.” Thomas then took little Peter into the garret where he slept, and bade him wait there till he brought him some fragments that he was freely permitted to take. The repast was a merry one, for Thomas was in high spirits, and little Peter had a famous appetite. “Ah,” cried Thomas, “here you are fed and lodged. Now the question is, how are you going to study?” “I shall study like all artists-with pencil and paper.” “But then, Peter, have you money to buy the paper and pencils?” “No, I have nothing; but I said to myself, ‘Thomas, who is scullion at his lordship’s, must have plenty of money!’ As you are rich, it is just the same as if I was.” Thomas scratched his head and replied, that as to broken victuals, he had plenty of them; but that he would have to wait three years before he should receive wages. Peter did not mind. The garret walls were white. Thomas could give him charcoal, and so he set to draw on the walls with that; and after a little while somebody gave Thomas a silver coin. With joy he brought it to his friend. Pencils and paper were bought. Early in the morning Peter went out studying the pictures in the galleries, the statues in the streets, the landscapes in the neighborhood; and in the evening, tired and hungry, but enchanted with what he had seen, he crept back into the garret, where he was always sure to find his dinner hidden under the mattress, to keep it warm, as Thomas said. Very soon the first charcoal drawings were rubbed off, and Peter drew his best designs to ornament his friend’s room. One day Cardinal Sachetti, who was restoring his palace, came with the architect to the very top of the house, and happened to enter the scullion’s garret. The room was empty; but both Cardinal and architect were struck with the genius of the drawings. They thought they were executed by Thomas, and his Eminence sent for him. When poor Thomas heard that the Cardinal had been in the garret, and had seen what he called Peter’s daubs, he thought all was lost. “You will no longer be a scullion,” said the Cardinal to him; and Thomas, thinking this meant banishment and disgrace, fell on his knees, and cried, “Oh! my lord, what will become of poor Peter?” The Cardinal made him tell his story. “Bring him to me when he comes in to-night,” said he, smiling. But Peter did not return that night, nor the next, till at length a fortnight had passed without a sign of him. At last came the news that the monks of a distant convent had received and kept with them a boy of fourteen, who had come to ask permission to copy a painting of Raphael in the chapel of the convent. This boy was Peter. Finally, the Cardinal sent him as a pupil to one of the first artists in Rome. Fifty years afterwards there were two old men who lived as brothers in one of the most beautiful houses in Florence. One said of the other, “He is the greatest painter of our age.” The other said of the first, “He is a model for evermore of a faithful friend.” by Author Unknown “Caesar Giving Cleopatra the Throne of Egypt” (1637), painting by Pietro da Cortona, housed in the Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon in Lyon, France.

Pietro da Cortona, or Peter of Cortona, was born as Pietro Berrettini on 1 November 1596 in Cortona, Arezzo, Tuscany, Italy. He became an artistic Baroque painter and architect. Pietro da Cortona passed on at 72 years of age on 16 May 1669 in Rome, Italy. You Know Tom!

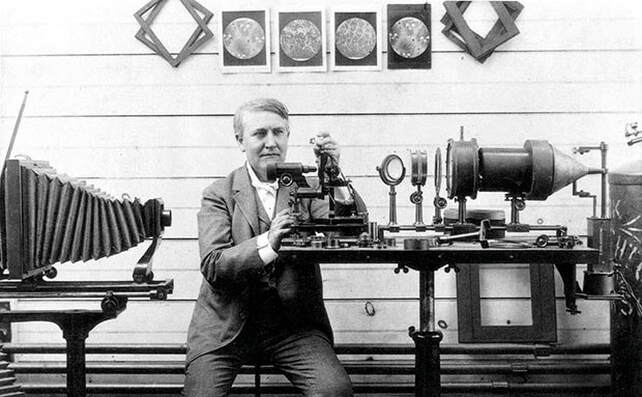

He’s the guy you run into everywhere, every day. Pick up a phone and there’s Tom. Turn on a light and there’s Tom. Bang on a keyboard and there’s Tom. Unwrap your sandwich and there’s Tom. Do any job and there’s Tom - helping you do it better . . . faster. Great guy, Thomas Alva Edison. You never think of him, though there are many things he invented. Most of them no longer bear his name. That’s okay with Tom; he didn’t care for credit lines. Tom is still very much alive because he started something that will never stop. He started America tinkering, forever tinkering with little things. Forever dissatisfied, forever improving. And that’s what makes America great! There are lots of Toms. Lots of guys and gals who are always alert to little ways of doing their job better, faster. Lots of people who know that the way to make the world a better place is to work like Tom. How about you? Thomas Alva Edison (tŏmꞋəs ălꞋvə/älꞋvä ĕdꞋĭ-sən) was born on 11 February 1847 in Milan, Ohio, United States of America. Although he was a school dropout, he is considered by many to have been the greatest inventor of all time, holding 1,093 United States patents. The ones that are perhaps best known are for a device for converting acoustic vibrations (sound) to fluctuating electrical signals that are transmitted through wires between telephones, called the carbon granule microphone (1877), a device for recording and playing back sound, called the phonograph (1878), and the first practical long lasting electric light, called the carbon filament incandescent lamp (1879). He was an entrepreneur and the founder of General Electric. Thomas Alva Edison passed on at 84 years of age on 18 October 1931 in West Orange, New Jersey, United States of America. Mary Anning was born on 21 May 1799 in Lyme Regis, Dorset, England, as a daughter of Mary ‘Molly’ Moore Anning and cabinetmaker Richard Anning. Her father frequently took Mary and her brother Joseph on fossil-hunting expeditions. To help their family make ends meet, they would place their discoveries on a table outside their home and offer them for sale to tourists. When Mary was 11 years of age, her father passed on. Mary Anning and her brother Joseph Anning (born 1796) were the only two of the ten children in the family to survive into adulthood. She continued in the family fossil hunting business, discovering skeletons of Jurassic marine animals including ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and various fishes in the collapsing seaside cliffs along the English channel. In 1826, at 27 years of age, she opened the Anning’s Fossil Depot, where she displayed and sold her fossil finds. Mary would eventually become known as one of the most famous of all fossil hunters, dealers, and paleontologists. However, during her lifetime, she was never taken as seriously as perhaps she could have been because she was a woman from a poor background, while most scientists at the time were men from wealthy families. Mary Anning passed on at 47 years of age on 9 March 1847 in Lyme Regis, Dorset, England, and rests in Saint Michael the Archangel Churchyard, Lyme Regis, Dorset, England. In an article in the February 1865 edition of his magazine, “All the Year Round,” Charles Dickens said of her, “The carpenter’s daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.”

The Story of Johnny Appleseed

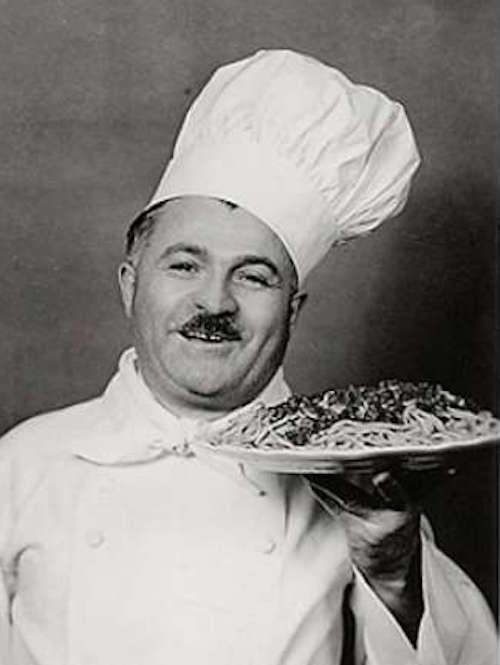

They called me Johnny Appleseed, but my real name was John Chapman. I was born on 26 September 1774, near Leominster, Massachusetts. I was a pretty smart kid, and learning made a big difference in my life. When I was 24 or 25, I became a nurseryman. That’s someone who works with plants. I liked apple trees, and I planted them on the western side of New York and Pennsylvania. Some of the big orchards you can see there today started with my trees. I was always looking for new places. In the early 1800s, I was one of the first to explore the rich, fertile lands south of the Great Lakes and west of the Ohio River when they were opened for settlers. They later called it the Northwest Territory - what became the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois. I called this big territory home for almost half a century - that’s 50 years. The settlers named me Johnny Appleseed. Some called me the Apple Tree Man, because I had lots of apple trees to sell to people so they could start their own orchards. Here’s how I did it: I went into the wilderness with a bag of apple seeds slung over my back. I’d walk around until I found a good place to plant my trees. Of course, I had to clear the land and chop brush and weeds by hand. Then, I’d plant my seeds in nice, neat rows and build a brush fence around them to keep animals from digging them up or eating them before they got a chance to grow. Some of my nurseries were about an acre or so. Others were quite a bit bigger. I did it all by myself. I wasn’t too lonely, though, because I had native tribes people for friends and wild animals for companions. I believed God would take care of me, and I lived by the Golden Rule: Always treat others as you want to be treated. There’s a story they tell about me that you might like: Once, I was caught in a really bad snowstorm and I took refuge in a big, hollow tree that had fallen to the ground. I was surprised to find a mother bear and her cubs already in there! Still, I needed to get out of the snowstorm, so we just shared that tree all night long. It wasn’t always an easy life, but all I had to do was think about that wilderness filled with the sweet-smelling blossoms of apple trees, and think about how delicious those apples would be to the families who planted them around their log cabins, and I knew it was worth it. I only charged a few pennies each for my trees, so everyone could afford fresh fruit. Some people had no pennies to spare, so I let them have their trees and told them they could pay me later. Not everybody could, but I had the satisfaction of knowing the trees were growing tall and strong, and that made me happy. My life wasn’t easy, but I loved it. I carried around a stewpot or kettle with me everywhere I went, and I sometimes wore it as a sort of hat. I didn’t eat meat, so I gathered berries and nuts. Sometimes people would give me milk from their dairy cows and potatoes from their gardens. Those were real treats. Most of the time, I walked on my journeys, but I sometimes used a canoe or raft to help carry load of seeds and seedlings along the rivers. I’d get those seeds from the cider presses of Pennsylvania, where they used machines to turn apples into a wonderful drink called apple cider. I never found a wife nor had children, but I had more friends than most people. Their families invited me to dinner at their homes and let me tell stories. I lived a long, happy life, living in the great outdoors and enjoying the majesty of God’s creations, until He called me home at 70 years of age on 18 March 1845. I hope you’ve enjoyed reading my story, and that you will remember that one person can make a big, big difference in the world. Just think of how many thousands of people planted my trees or ate my apples! Ask your friends if they know who Johnny Appleseed is, and see what they say. Find your job, and maybe someday, people will be telling the story of your life! by Author Unknown: an account of the life of John Chapman John Chapman, commonly known by the nickname Johnny Appleseed, was born on 26 September 1774 in Leominster, Worcester County, Massachusetts, British Colonial America. He became a nurseryman and a missionary for The New Church, or Swedenborgian, denomination of Christianity. He bought apple seeds from cider mills, and traveled on foot ahead of settlers in order to plant the seeds and thereby claim the land under the homestead laws of the time, later selling his apple trees and land to settlers. He planted apple trees from seed in parts of Pennsylvania, Ontario, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and what is now known as West Virginia. John Chapman passed on at 70 years of age on 18 March 1845 in Fort Wayne, Allen County, Indiana, United States of America, and rests somewhere in the vicinity of Johnny Appleseed Memorial Park, Fort Wayne, Allen County, Indiana, United States of America. The Story of Chef Boyardee Who is Chef Boyardee? Ettore J. ‘Hector’ Boiardi was born on 22 October 1897 in Piacenza, Provincia di Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna, Italy. At 11 years of age, he began working as an apprentice chef in a hotel in Piacenza. At 16 years of age, on 9 May 1914, he arrived at Ellis Island aboard the ship “La Lorraine,” and he and his brother Paolo ‘Paul’ Boiardi went to work in the kitchen at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. Eventually, the young cook worked his way up to become the head chef. By 1915, Hector Boiardi was in charge of food catering for the wedding of American President Woodrow Wilson, at the Greenbrier Hotel in West Virginia, and he later supervised the catering of the homecoming meal for 2,000 World War One soldiers at the White House. In 1923, he married Helen Wroblewski, and together the couple had one son. At 28 years of age, in 1926, Hector Boiardi opened his Il Giardino d’Italia (English: The Garden of Italy) restaurant in Cleveland, Ohio. His customers asked for bottles of his pasta sauce so that they could serve it at home, and he obliged. He then added cheeses and pasta to the sauce. In 1927, he met and collaborated with two of his restaurant patrons, Maurice and Eva Weiner, owners of a chain of self-service grocery stores, to begin making his food products on a larger scale. Mr. Boiardi and his brothers Mario Boiardi and Paolo ‘Paul’ Boiardi began to process first sauces and then other foods, at a canning plant for distribution across the United States. The popularity of Hector Boiardi’s products led to an expanded factory in 1928, and by 1929 he was selling his spaghetti products nationwide. A decade later, in 1938, the Boiardi family moved their company to Milton, Pennsylvania, where they began to grow fresh produce, including tomatoes and mushrooms, as ingredients in their food products. It was during this time that Mr. Boiardi began to sell his packaged products with the name ‘Chef Boyardee,’ so that his customers could more easily pronounce his Italian name. Hector Boiardi sold his company for just under 6 million dollars in 1946 to American Home Foods (which later became International Home Foods), though continuing to be involved as an advisor in their canned pasta business for the remainder of his life. Mr. Boiardi’s name, spelled phonetically as ‘Boyardee’ and his likeness are still on the food labels. Ettore J. ‘Hector’ Boiardi passed on at 87 years of age on 21 June 1985 in Parma, Ohio, United States of America. His life’s work is available at your favorite market or internet retailer, and you can also find out where it is available near you by visiting the Chef Boyardee website at www.ChefBoyardee.com. The name ‘Chef Boyardee’ and likenesses of Ettore J. ‘Hector’ Boiardi are trademarked properties of ConAgra Foods.

What will be your life’s work, where will it take you, and what will coming generations say about you? |

Life

Time

Work

Do you need a joke, quotation, paragraph, or poem about a particular subject or topic? Go to the search box found at the top right side of this page and type it in. We have a surprising variety of material and we add new stuff regularly, so you might find what you are seeking.

Make Fun Of Life! can be right there with you, at home or wherever you go, on a laptop, cell phone, tablet, or any other internet connected device. Bookmark us and visit whenever you can. We regularly add fascinating new articles just for you!

You are now on the Make Fun Of Life! Website . . . where humor, inspiration, and learning are back together again - as they were always meant to be.

Welcome to the Make Fun Of Life! Website. We are here to bring a little happiness to the world. Would you like to be among the first people to see new articles when they appear on the website? Click on the social media buttons on the left side of your screen and then follow us. We wish you the very best imaginable day, and thank you for visiting!

|